Rust Tiếng Việt

The book is published at https://rust-tieng-viet.github.io.

_~^~^~_

\) / o o \ (/

'_ _ _'

/ '-----' \

Rust là một ngôn ngữ nhanh, an toàn và được bình chọn là ngôn ngữ được ưa thích nhất trong nhiều năm liền theo Stack Overflow Survey. Rust có một hệ thống tài liệu và sách đồ sộ, chi tiết. Nhưng đôi khi nó sẽ khó tiếp cận với một số người bởi đa số tài liệu là Tiếng Anh. Với những ghi chép trong sách này, hy vọng có thể giúp cho mọi người (cũng như các thành viên trong team mình tại Fossil) có thể tiếp cận với ngôn ngữ này một cách nhanh chóng và dễ dàng hơn. Cũng như truyền cảm hứng và mở rộng cộng đồng sử dụng Rust tại Việt Nam.

Mục tiêu của sách này không phải là dịch từ các sách tiếng Anh.

Mà sẽ là những ghi chép, những lưu ý cho một người mới bắt đầu học Rust

cho đến lúc thành thạo, từ lúc hello world cho đến các dự án thực tế.

Bao gồm những khó khăn mà bạn sẽ phải gặp, những thuật ngữ, concepts mới,

những thói quen lập trình mới mà bạn sẽ phải làm quen.

Mình vẫn luôn prefer đọc sách tiếng Anh nếu bạn có thể. Vui lòng xem mục references ở cuối các trang nếu bạn muốn đào sâu hơn.

Links

Cài đặt Rust

Dưới đây là hướng dẫn chi tiết về cách cài đặt Rust trên hệ điều hành Windows, macOS và Linux. Bạn cũng có thể tự tham khảo trên trang chủ của Rust: https://www.rust-lang.org/tools/install

Cài đặt Rust trên macOS, Linux

Mở Terminal và chạy lệnh sau:

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://sh.rustup.rs | sh

Sau khi hoàn thành quá trình cài đặt, bạn có thể kiểm tra phiên bản Rust bằng cách mở Terminal và chạy lệnh sau:

rustc --version

Cài đặt Rust trên Windows

Để tải xuống trình cài đặt Rust, bạn cần truy cập vào trang web chính thức của Rust tại địa chỉ https://forge.rust-lang.org/infra/other-installation-methods.html

Chạy tập tin rustup-init.exe để bắt đầu quá trình cài đặt Rust trên máy tính của mình.

References

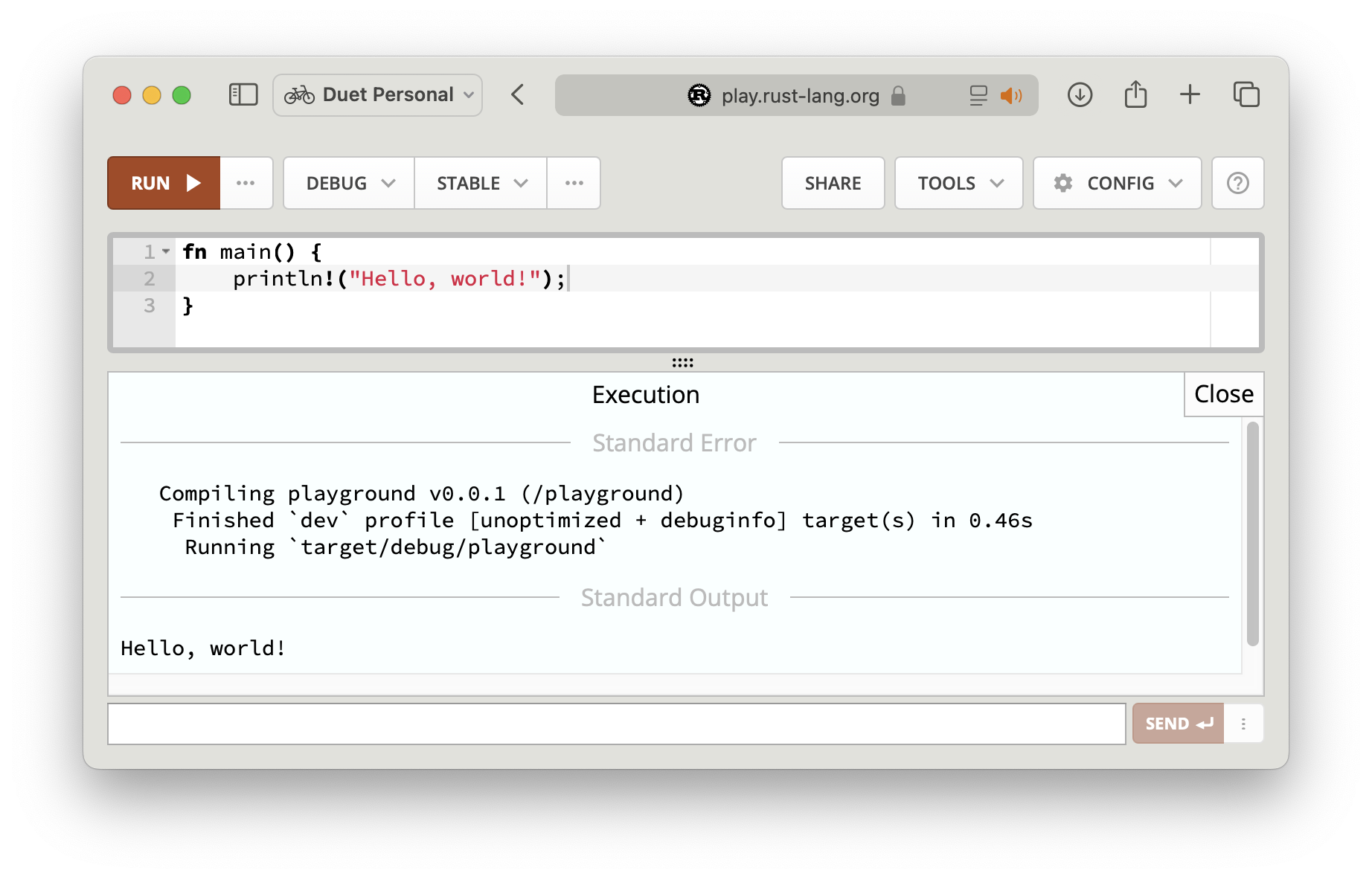

Rust Playground

https://play.rust-lang.org giúp chúng ta chạy Rust code trực tiếp trên trình duyệt mà không cần cài đặt Rust trên máy.

Một số tips:

- Bấm Run để chạy code. Có thể chuyển đổi giữa các version của Rust.

- Chọn Release thay vì Debug để chạy nhanh hơn (nhưng thiếu một số thông tin debug).

- Chọn Share để chia sẻ link đoạn code với người khác.

- Rustfmt sẽ tự động format code của bạn (như

cargo fmt). - Clippy sẽ kiểm tra code của bạn và đưa ra gợi ý (như

cargo clippy).

Project đầu tiên

Sau khi cài đặt Rust thành công, bạn có thể bắt đầu sử dụng Cargo (một công cụ quản lý gói mạnh mẽ được tích hợp sẵn trong Rust) để khởi tạo project hello world đầu tiên.

Bước 1: Tạo một package mới

Để bắt đầu với Cargo, bạn cần tạo một package mới bằng lệnh cargo new <name>. Ví dụ, để tạo một package mới với tên là hello_world, bạn chạy lệnh sau đây:

$ cargo new hello_world

# Created binary (application) `hello_world` package

Cargo sẽ tạo ra một package mới với một file Cargo.toml và một thư mục src. File Cargo.toml chứa tất cả các thông tin liên quan đến package của bạn.

$ tree .

.

├── Cargo.toml

└── src

└── main.rs

2 directories, 2 files

Hãy xem nội dung của src/main.rs

fn main() {

println!("Hello, world!");

}Bước 2: Biên dịch và chạy chương trình

Tiếp theo, để biên dịch chương trình của bạn, hãy chạy lệnh cargo build. Sau khi quá trình biên dịch kết thúc, Cargo sẽ tạo ra một thư mục mới có tên target, chứa tệp thực thi của chương trình.

$ cargo build

# Compiling hello_world v0.1.0 (/Users/duyet/project/hello_world)

# Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.67s

Để chạy chương trình, bạn có thể sử dụng lệnh ./target/debug/<name>. Ví dụ, để chạy chương trình hello_world, bạn có thể chạy lệnh sau đây:

$ ./target/debug/hello_world

# Hello, world!

Kết quả sẽ hiển thị trên màn hình là “Hello, world!”. Ngoài ra, bạn cũng có thể biên dịch và chạy chương trình chỉ trong một bước bằng cách sử dụng lệnh cargo run.

$ cargo run

# Hello, world!

References

Variables

Variables trong Rust có kiểu dữ liệu tĩnh. Ta khai báo kiểu dữ liệu trong lúc khai báo biến. Trong đa số các trường hợp compiler có thể đoán được kiểu dữ liệu nên đôi khi ta có thể bỏ qua.

fn main() {

let an_integer = 1u32;

let a_boolean = true;

let unit = ();

// copy `an_integer` into `copied_integer`

let copied_integer = an_integer;

}Mọi biến đều phải được sử dụng, nếu không, compiler sẽ warning. Để skip warning, thêm dấu underscore ở đầu tên biến.

fn check_error() {}

fn main() {

// The compiler warns about unused variable bindings; these warnings can

// be silenced by prefixing the variable name with an underscore

let _unused_variable = 3u32;

// Skip the result of function

let _ = check_error();

}mut

Mọi biến trong Rust mặc định là immutable, có nghĩa là không thể thay đổi, không thể gán bằng một giá trị khác.

fn main() {

let a = 1;

a = 2;

}

// error[E0384]: cannot assign twice to immutable variable `a`

// --> src/main.rs:4:1

// |

// 3 | let a = 1;

// | -

// | |

// | first assignment to `a`

// | help: consider making this binding mutable: `mut a`

// 4 | a = 2;

// | ^^^^^ cannot assign twice to immutable variableĐể có thể thay đổi giá trị của biến, ta thêm từ khóa mut sau let.

fn main() {

let mut a = 1;

a = 2;

println!("a = {}", a);

}Ta cũng có thể khai báo lại biến đó để assign lại giá trị mới:

fn main() {

let a = 1;

let a = a + 1;

}Scope

Giá trị của variables có thể được xác định tùy theo scope.

Scope là một tập hợp các dòng code nằm trong {}.

let a = 1;

{

let a = 2;

println!("inner: a = {}", a); // 2

}

println!("outer: a = {}", a); // 1Return trong scope

Ta cũng có thể return giá trị trong một scope cho một variable.

let a = {

let y = 10;

let z = 100;

y + z

};

println!("a = {}", a);mut

mut

Mọi biến trong Rust mặc định là immutable, có nghĩa là không thể thay đổi, không thể gán bằng một giá trị khác.

fn main() {

let a = 1;

a = 2;

}

// error[E0384]: cannot assign twice to immutable variable `a`

// --> src/main.rs:4:1

// |

// 3 | let a = 1;

// | -

// | |

// | first assignment to `a`

// | help: consider making this binding mutable: `mut a`

// 4 | a = 2;

// | ^^^^^ cannot assign twice to immutable variableĐể có thể thay đổi giá trị của biến, ta thêm từ khóa mut sau let.

fn main() {

let mut a = 1;

a = 2;

println!("a = {}", a);

}Ta cũng có thể khai báo lại biến đó để assign lại giá trị mới:

fn main() {

let a = 1;

let a = a + 1;

}uninitialized variable

Variable mà chưa được gán giá trị được gọi là uninitialized variable.

fn main() {

let my_variable; // ⚠️

}Rust sẽ không compile và bạn sẽ không thể sử dụng cho đến khi my_variable được gán giá trị nào đó. Ta có thể lợi dụng điều này:

- Khai báo uninitialized variable.

- Gán giá trị cho nó trong 1 scope khác

- Vẫn giữ được giá trị của của variable đó khi ra khỏi scope.

fn main() {

let my_number;

{

my_number = 100;

}

println!("{}", my_number);

}Hoặc phức tạp hơn

fn loop_then_return(mut counter: i32) -> i32 {

loop {

counter += 1;

if counter % 50 == 0 {

break;

}

}

counter

}

fn main() {

let my_number;

{

// Pretend we need to have this code block

let number = {

// Pretend there is code here to make a number

// Lots of code, and finally:

57

};

my_number = loop_then_return(number);

}

println!("{}", my_number); // 100

}Closure

Hay còn được gọi là anonymous functions hay lambda functions. Khác với function bình thường, kiểu dữ liệu của tham số đầu vào và kiểu dữ liệu trả ra là không bắt buộc.

Function bình thường:

fn get_square_value(i: i32) -> i32 {

i * i

}

fn main() {

let x = 2;

println!("{}", get_square_value(x));

}Closure:

fn main() {

let x = 2;

let square = |i: i32| -> i32 {

i * i

};

println!("{}", square(x));

}Closure không cần data type

fn main() {

let x = 2;

let square = |i| {

i * i

};

println!("{}", square(x));

}Tham số của của closure được đặt giữa 2 dấu: | và |.

Closure không có tham số

Với closure không có tham số, ta viết như sau:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let func = || { 1 + 1 };

}Closure chỉ có một mệnh đề

Dấu ngoặc {} cũng không bắt buộc nếu nội dung của closure chỉ có một mệnh đề.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let func = || 1 + 1;

}Vừa định nghĩa, vừa thực thi

fn main() {

let x = 2;

let square = |i| -> i32 { // ⭐️ nhưng bắt buộc khai báo return type

i * i

}(x);

println!("{}", square);

}Cargo

cargo là package management tool official của Rust.

cargo có rất nhiều tính năng hữu ích để improve code quality và nâng cao tốc độ của lập trình viên.

cargo có hẳn một quyển sách riêng: The Cargo Book

Những tính năng phổ biến mà bạn sẽ phải dùng hằng ngày:

cargo add <crate>: cài đặt crate mới từ https://crates.io, crate sẽ được thêm vàoCargo.toml.cargo rhoặccargo run: biên dịch và chạy chương trình (main.rs).cargo thoặccargo test: run mọi tests (unit tests, doc tests, integration tests).cargo fmt: format code.cargo clippy: lint để bắt các lỗi phổ biến trong lập trình, code đẹp hơn, chạy nhanh hơn, etc. https://github.com/rust-lang/rust-clippy

Packages và Crates

Package là một hoặc nhiều crates. Một package gồm một file Cargo.toml mô tả cách để build các crates đó.

Crate có thể là một binary crate hoặc library crate.

- binary crate có thể được compile thành binary và có thể thực thi được, ví dụ như một command-line hoặc server. Một binary crate bắt buộc phải có một hàm

main() - library crate không cần hàm

main(). Library crate dùng để share các tính năng cho các project khác.

Package layout

Được mô tả trong Cargo book, một crate trong Rust sẽ có layout như sau:

.

├── Cargo.lock

├── Cargo.toml

├── src/

│ ├── lib.rs

│ ├── main.rs

│ ├── helper.rs

│ ├── utils/

│ │ ├── mod.rs

│ │ └── math.rs

│ └── bin/

│ ├── named-executable.rs

│ └── another-executable.rs

├── benches/

│ ├── large-input.rs

│ └── multi-file-bench.rs

├── examples/

│ ├── simple.rs

│ └── complex.rs

└── tests/

├── some-integration-tests.rs

└── multi-file-test/

├── main.rs

└── test_module.rs

Cargo.tomlvàCargo.lockdược đặt ở thư mục gốc của package. Thường để sử dụng các library nào đó, người ta sẽ hướng dẫn bạn thêm một dòng ví dụlog = "0.6"bên dưới section[dependencies]hoặc[dev-dependencies]. Không nên đụng đến fileCargo.lockdo nó được generate tự động.- Source code được đặt trong thư mục

src. - File chính của library crate là

src/lib.rs. - File chính của binary crate là

src/main.rs. - Benchmark code được đặt trong thư mục

benches. - Code ví dụ (examples) được đặt trong thư mục

examples. - Integration tests được đặt trong thư mục

tests. helper.rsvàutils/được gọi là các module. Nếu module là một thư mục gồm nhiều file khác, filemod.rsđược coi như là file index của module đó. Xem thêm về modules tại đây.

Crate

Crate có thể là một binary crate hoặc library crate.

- binary crate có thể được compile thành binary và có thể thực thi được, ví dụ như một command-line hoặc server. Một binary crate bắt buộc phải có một hàm

main() - library crate không cần hàm

main(). Library crate dùng để share các tính năng cho các project khác.

Crate được publish trên https://crates.io.

Init crate

Để tạo một crate mới ta sử dụng cargo:

cargo new crate_name: binary crate.cargo new crate_name --lib: library crate.

Layout của binary crate và library crate

// Binary crate

├── Cargo.toml

└── src

└── main.rs

// Library crate

├── Cargo.toml

└── src

└── lib.rs

Một crate có thể vừa có lib.rs và main.rs.

Binary crate khi cargo build hoặc cargo run sẽ build ra một file binary bỏ trong ./target/debug/<crate_name>.

Khi build cho môi trường production, ta thêm --release lúc này cargo sẽ build thành binary bỏ trong ./target/release/<crate_name>.

debug hay release được gọi là các build target. Build trong release sẽ được apply nhiều optimization hơn, kích thước nhỏ hơn, chạy nhanh hơn nhưng compile lâu hơn.

use crate

Để sử dụng (import) một crate từ https://crates.io, ví dụ https://crates.io/crates/log.

1. Thêm crate vào Cargo.toml

Có 2 cách

Cách 1: Edit trực tiếp file Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

log = "0.4"

Cách 2: Sử dụng cargo add, cargo sẽ tự động update file Cargo.toml cho bạn

cargo add log

[dependencies]

log = "0.4.17"

Để thêm crate vào dev dependencies (dùng cho tests), ta thêm --dev vào lệnh:

cargo add --dev log

[dev-dependencies]

log = "0.4.17"

2. Sử dụng crate trong code

fn main() {

log::info!("hello");

log::error!("oops");

}Sử dụng keyword use. Chức năng chính của use là bind lại full path

của element vào một tên mới, để chúng ta không cần phải lặp lại một tên dài mỗi lần sử dụng.

use log::info;

use log::error;

fn main() {

info!("hello");

error!("oops");

}Nhóm các import lại với nhau:

use log::{info, error};

fn main() {

info!("hello");

error!("oops");

}Import mọi thứ được public trong crate/module. Cách này thường hay tránh bởi

sẽ khó biết được function, struct, … nào đó đang thuộc crate nào, ngoại trừ các prelude::*.

use log::*;

fn main() {

info!("hello");

error!("oops");

}use trong scope

use cũng thường được sử dụng import element vào trong scope hiện tại.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn hello() -> String {

"Hello, world!".to_string()

}

#[cfg(test)]

mod tests {

use super::hello; // Import the `hello()` function into the scope

#[test]

fn test_hello() {

assert_eq!("Hello, world!", hello()); // If not using the above `use` statement, we can run same via `super::hello()`

}

}

}Bạn sẽ sẽ hay gặp:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// ...

#[cfg(test)]

mod tests {

use super::*;

use log::info;

// ...

}

}self::, super::

Mặc định thì use sẽ import đường dẫn tuyệt đối, bắt đầu từ crate root.

self và super thường dùng để import mod theo vị trí tương đối.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// src/level_1/level_2/mod.rs

use self::hello_1;

use super::super::level3::hello_2;

}Re-export

Một trường hợp đặt biệt là sử dụng pub use là re-exporting,

khi bạn thiết kế một module bạn có thể export một số thứ từ module khác (*) từ module của bạn.

Do đó người sử dụng có thể sử dụng các module khác đó ngay từ module của bạn.

Module khác (*) đó có thể là một internal module, internal crate hoặc external crate.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// src/utils.rs

pub use log::*;

}// src/main.rs

use crate::utils::info;

fn main() {

info!("...");

}Pattern này được sử dụng khá nhiều ở các thư viện lớn. Nó giúp ẩn đi các internal module phức tạp của library đối với user. Bởi vì user sẽ không cần quan tâm đến cấu trúc directory phức tạp khi sử dụng một library nào đó.

use self, use super

self::, super::

Mặc định thì use sẽ import đường dẫn tuyệt đối, bắt đầu từ crate root.

self và super thường dùng để import mod theo vị trí tương đối.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// src/level_1/level_2/mod.rs

use self::hello_1;

use super::super::level3::hello_2;

}pub use

Re-export

Một trường hợp đặt biệt là sử dụng pub use là re-exporting,

khi bạn thiết kế một module bạn có thể export một số thứ từ module khác (*) từ module của bạn.

Do đó người sử dụng có thể sử dụng các module khác đó ngay từ module của bạn.

Module khác (*) đó có thể là một internal module, internal crate hoặc external crate.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// src/utils.rs

pub use log::*;

}// src/main.rs

use crate::utils::info;

fn main() {

info!("...");

}Pattern này được sử dụng khá nhiều ở các thư viện lớn. Nó giúp ẩn đi các internal module phức tạp của library đối với user. Bởi vì user sẽ không cần quan tâm đến cấu trúc directory phức tạp khi sử dụng một library nào đó.

Preludes

Preludes là những thứ được định nghĩa trong std,

và được import sẵn, vì chúng thường sẽ phải được dùng trong mọi chương trình Rust.

Bạn có thể sử dụng mà không cần phải import, ví dụ như: Option,

Result, Ok, Err, …

Mặc dù std của Rust có rất nhiều module và tính năng, nhưng không phải mọi thứ đều được preludes.

Đây là danh sách những thứ được preludes: https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/prelude/#prelude-contents

std::marker::{Copy,Send,Sized,Sync,Unpin}std::ops::{Drop,Fn,FnMut,FnOnce}().std::mem::dropstd::boxed::Boxstd::borrow::ToOwnedto_owned, the generic method for creating an owned type from a borrowed type.std::clone::Cloneclone, the method for producing a copy of a value.std::cmp::{PartialEq,PartialOrd,Eq,Ord}std::convert::{AsRef,AsMut,Into,From}std::default::Defaultstd::iter::{Iterator,Extend,IntoIterator,DoubleEndedIterator,ExactSizeIterator}std::option::Option::{self,Some,None}std::result::Result::{self,Ok,Err}Option, its variants are exported as well.std::string::{String,ToString}std::vec::Vec

The prelude used in Rust 2021, std::prelude::rust_2021, includes all of the above,

and in addition re-exports:

Ownership

Ownership là một trong những tính năng đặc trưng của Rust, đây là cách giúp Rust đảm bảo memory safety mà không cần đến garbage collector.

Ownership là gì?

Ownership là một khái niệm mới. Tất cả các chương trình đều cần phải quản lý bộ nhớ mà chúng sử dụng trong quá trình thực thi. Một số ngôn ngữ sử dụng garbage collection để tìm và giải phóng bộ nhớ trong thời gian chạy, trong khi một số ngôn ngữ khác yêu cầu lập trình viên tự cấp phát (allocate) và giải phóng (free) bộ nhớ. Rust đi theo một hướng khác, trong đó bộ nhớ được quản lý bởi một hệ thống ownership với các quy tắc mà trình biên dịch sử dụng để kiểm tra (check) trong quá trình biên dịch. Bằng cách này, Rust buộc chúng ta phải viết mã theo cách an toàn cho bộ nhớ, và sẽ phát hiện lỗi ngay trong quá trình biên dịch. Càng hiểu rõ về khái niệm ownership, chúng ta càng có thể viết mã an toàn và hiệu quả hơn.

Để tìm hiểu kỹ hơn về Ownership, bạn có thể đọc Rust Book tại đây cực kỳ chi tiết: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch04-01-what-is-ownership.html

Ownership Rules

Nói đơn giản về ownership rules thì có một số điều cơ bản sau:

- Mỗi giá trị trong Rust đều có một biến gọi là owner của nó.

- Chỉ có một owner tại một thời điểm.

- Khi owner ra khỏi scope, giá trị sẽ bị hủy.

Borrow checker

Bằng cách theo dõi data sử dụng thông qua bộ rules,

borrow checker có thể xác định khi nào data cần được khởi tạo

(initialized) và khi nào cần được giải phóng (freed, or dropped).

Thực tế sẽ có một trong ba trường hợp sau khi bạn sử dụng variable:

tự move data và bỏ ownership; copy data sang một variable khác;

hoặc sử dụng reference (con trỏ) đến data và vẫn giữ ownership,

cho mượn (borrow) nó một thời gian.

Chỉ cần nhớ hai quy tắc quan trọng:

- Khi truyền một variable (thay vì reference tới variable) cho một function khác, ta sẽ mất quyền ownership. Function đó sẽ là owner của variable này và bạn không thể sử dụng lại được nữa ở context cũ.

- Khi truyền một reference tới variable, bạn có thể immutable borrow không giới hạn; hoặc mutable borrow một lần.

Ví dụ: đoạn chương trình sau sẽ không compile được

fn hold_my_vec<T>(_: Vec<T>) {}

fn main() {

let x = vec![1, 2, 3];

hold_my_vec(x);

let z = x.get(0);

println!("Got: {:?}", z);

}Compiler sẽ báo lỗi như sau: rustc main.rs

error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `x`

--> main.rs:7:13

|

4 | let x = vec![1, 2, 3];

| - move occurs because `x` has type `Vec<i32>`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

5 | hold_my_vec(x);

| - value moved here

6 |

7 | let z = x.get(0);

| ^^^^^^^^ value borrowed here after move

|

= note: borrow occurs due to deref coercion to `[i32]`Lỗi nói rằng Vec<i32> không implement

Copy trait,

vì thế data sẽ được di chuyển (move) hoặc mượn (borrow) vào function

hold_my_vec(). Do đó dòng 7 không thể thực hiện được do x được

được move vào trong function kia.

Mặc dùng không thể implement Copy trait, Vec vẫn có

Clone trait.

Chỉ để cho code chạy được thì đây là một cách nhanh để compiler ngưng báo lỗi.

Lưu ý thì việc clone thường sẽ tốn khá nhiều chi phí, nhất là đối với những object lớn.

fn hold_my_vec<T>(_: Vec<T>) {}

fn main() {

let x = vec![1, 2, 3];

hold_my_vec(x.clone()); // <-- x.clone()

let z = x.get(0);

println!("Got: {:?}", z);

}Trong trường hợp này, function hold_my_vec không làm gì ngoài việc nhận ownership.

Có một cách tốt hơn là references.

Thay vì để function nhận ownership, ta có thể cho nó mượn giá trị.

Chúng ta sẽ truyền vào một reference — một giá trị được mượn.

fn hold_my_vec<T>(_: &Vec<T>) {}

fn main() {

let x = vec![1, 2, 3];

hold_my_vec(&x); // <--- &x

let z = x.get(0);

println!("Got: {:?}", z);

}Với cách này thì chúng ta sẽ để function mượn trong khi vẫn có thể tiếp tục sử sử dụng trong chương trình.

Bạn có thể đọc thêm về Ownership, References and Borrowing và The Slice Type tại the Rust Book.

Struct

Struct được sử dụng trong Rust rất nhiều, hầu như là mọi lúc. Với struct ta có thể định nghĩa một kiểu dữ liệu riêng.

Tên của struct thường là UpperCamelCase. Nếu bạn định nghĩa tên struct là lowercase, compiler sẽ nhắc nhở ngay.

warning: type `duyet_struct` should have an upper camel case name

--> src/main.rs:1:8

|

1 | struct duyet_struct;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^ help: convert the identifier to upper camel case: `DuyetStruct`

|

= note: `#[warn(non_camel_case_types)]` on by default

Có 3 loại struct:

Unit struct

Unit struct là một struct mà không có gì cả:

struct FileDirectory;

fn main() {}Tuple struct

Tuple struct hay còn gọi là Unnamed struct. Bạn chỉ cần định nghĩa kiểu dữ liệu, không cần định tên field name.

struct Colour(u8, u8, u8);

fn main() {

let my_colour = Colour(50, 0, 50); // Make a colour out of RGB (red, green, blue)

println!("The first part of the colour is: {}", my_colour.0);

println!("The second part of the colour is: {}", my_colour.1);

}

// The first part of the colour is: 50

// The second part of the colour is: 0Named struct

Phổ biến nhất, bạn sẽ phải định nghĩa field name trong block {}

struct Colour(u8, u8, u8); // Declare the same Colour tuple struct

struct SizeAndColour {

size: u32,

colour: Colour, // And we put it in our new named struct

// The last comma is optional, but recommended

}

fn main() {

let colour = Colour(50, 0, 50);

let size_and_colour = SizeAndColour {

size: 150,

colour: colour

};

}colour: colour có thể được viết gọn lại thành:

let size_and_colour = SizeAndColour {

size: 150,

colour

};Xem về Trait

Trait

Rust có nhiều loại data types như primitives (i8, i32, str, …), struct, enum và các loại kết hợp (aggregate) như tuples và array. Mọi types không có mối liên hệ nào với nhau. Các data types có các phương thức (methods) để tính toán hay convert từ loại này sang loại khác, nhưng chỉ để cho tiện lợi hơn, method chỉ là các function. Bạn sẽ làm gì nếu một tham số là nhiều loại kiểu dữ liệu? Một số ngôn ngữ như Typescript hay Python sẽ có cách sử dụng Union type như thế này:

function notify(data: string | number) {

if (typeof data == 'number') {

// ...

} else if (typeof data == 'number') {

// ...

}

}

Còn trong Rust thì sao?

Trait là gì?

Có thể bạn đã thấy qua trait rồi: Debug, Copy, Clone, … là các trait.

Trait là một cơ chế abstract để thêm các tính năng (functionality) hay hành vi (behavior) khác nhau vào các kiểu dữ liệu (types) và tạo nên các mối quan hệ giữa chúng.

Trait thường đóng 2 vai trò:

- Giống như là interfaces trong Java hay C# (fun fact: lần đầu tiên nó được gọi là

interface). Ta có thể kế thừa (inheritance) interface, nhưng không kế thừa được implementation của interface*.* Cái này giúp Rust có thể hỗ trợ OOP. Nhưng có một chút khác biệt, nó không hẳn là interface. - Vai trò này phổ biến hơn, trait đóng vai trò là generic constraints. Dễ hiểu hơn, ví dụ, bạn định nghĩa một function, tham số là một kiểu dữ liệu bất kỳ nào đó, không quan tâm, miễn sau kiểu dữ liệu đó phải có phương thức

method_this(),method_that()nào đó cho tui. Kiểu dữ liệu nào đó gọi là genetic type. Function có chứa tham số generic type đó được gọi là generic function. Và việc ràng buộc phải cómethod_this(),method_that(), … gọi là generic constraints. Mình sẽ giải thích rõ cùng với các ví dụ sau dưới đây.

Để gắn một trait vào một type, bạn cần implement nó.

Bởi vì Debug hay Copy quá phổ biến, nên Rust có attribute để tự động implement:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[derive(Debug)]

struct MyStruct {

number: usize,

}

}Nhưng một số trait phức tạp hơn bạn cần định nghĩa cụ thể

bằng cách impl nó. Ví dụ bạn có trait Add

(std::ops::Add)

để add 2 type lại với nhau. Nhưng Rust sẽ không biết cách bạn add 2

type đó lại như thế nào, bạn cần phải tự định nghĩa:

use std::ops::Add;

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq)]

struct MyStruct {

number: usize,

}

impl Add for MyStruct { // <-- here

type Output = Self;

fn add(self, other: Self) -> Self {

Self { number: self.number + other.number }

}

}

fn main() {

let a1 = MyStruct { number: 1 };

let a2 = MyStruct { number: 2 };

let a3 = MyStruct { number: 3 };

assert_eq!(a1 + a2, a3);

}Note: Mình sẽ gọi Define Trait là việc định nghĩa,

khai báo một trait mới trong Rust (trait Add).

Implement Trait là việc khai báo nội dung của function được

liệu kê trong Trait cho một kiểu dữ liệu cụ thể nào đó (impl Add for MyStruct).

Chi tiết

- Khai báo Trait

- Implement Trait cho một Type

- Default Implementations

- Traits as Parameters

- Trait Bound

- Multiple Trait Bound

whereClauses- Returning Types that Implement Traits

- Using Trait Bounds to Conditionally Implement Methods

- Blanket implementations

- Trait Inheritance

- Supertraits

- Auto Trait

- Copy, Clone

- String và &str

- FromStr

- Display

Kết

Compiler sử dụng trait bound để kiểm tra các kiểu dữ liệu được sử dụng trong code có đúng behavior không. Trong Python hay các ngôn ngữ dynamic typed khác, ta sẽ gặp lỗi lúc runtime nếu chúng ta gọi các method mà kiểu dữ liệu đó không có hoặc không được định nghĩa.

Bạn có chắc chắn là a dưới đây có method summarize() hay không?

Nhớ rằng typing hint của Python3 chỉ có tác dụng là nhắc nhở cho lập trình viên thôi.

# Python

func print_it(a: Union[NewsArticle, Tweet]):

print(a.summarize())

print_it(1)

print_it("what")

Do đó Rust bắt được mọi lỗi lúc compile time và force chúng ta phải fix hết trước khi chương trình chạy. Do đó chúng ta không cần phải viết thêm code để kiểm tra behavior (hay sự tồn tại của method) trước khi sử dụng lúc runtime nữa, tăng cường được performance mà không phải từ bỏ tính flexibility của generics.

Xem về Struct.

Khai báo / định nghĩa một Trait

Nhắc lại là Trait định nghĩa các hành vi (behavior). Các types khác nhau có thể chia sẻ cùng cá hành vi. Định nghĩa một trait giúp nhóm các hành vi để làm một việc gì đó.

Theo ví dụ của Rust Book, ví dụ ta các struct chứa nhiều loại text:

NewsArticlestruct chứa news story, vàTweetstruct có thể chứa tối đa 280 characters cùng với metadata.

Bây giờ chúng ta cần viết 1 crate name có tên là aggregator

có thể hiển thị summaries của data có thể store trên NewsArticle

hoặc Tweet instance. Chúng ta cần định nghĩa method summarize

trên mỗi instance. Để định nghĩa một trait, ta dùng trait theo sau

là trait name; dùng keyword pub nếu định nghĩa một public trait.

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize(&self) -> String;

}Trong ngoặc, ta định nghĩa các method signatures để định nghĩa hành vi:

fn summarize(&self) -> String. Ta có thể định nghĩa nội dung của function.

Hoặc không, ta dùng ; kết thúc method signature, để bắt buộc type nào

implement trait Summary đều phải định nghĩa riêng cho nó,

bởi vì mỗi type (NewsArticle hay Tweet) đều có cách riêng để summarize. Mỗi trait có thể có nhiều method.

Implement Trait cho một Type

Bây giờ ta định implement các method của trait Summary cho từng type.

Ví dụ dưới đây ta có struct NewsArticle và struct Tweet,

và ta định nghĩa summarize cho 2 struct này.

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize(&self) -> String;

}

pub struct NewsArticle {

pub headline: String,

pub location: String,

pub author: String,

pub content: String,

}

impl Summary for NewsArticle {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}, by {} ({})", self.headline, self.author, self.location)

}

}

pub struct Tweet {

pub username: String,

pub content: String,

pub reply: bool,

pub retweet: bool,

}

impl Summary for Tweet {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}: {}", self.username, self.content)

}

}Implement trait cho type giống như impl bình thường,

chỉ có khác là ta thêm trait name và keyword for sau impl.

Bây giờ Summary đã được implement cho NewsArticle và Tweet,

người sử dụng crate đã có thể sử dụng các phương thức của trait như các method function bình thường.

Chỉ một điều khác biệt là bạn cần mang trait đó vào cùng scope hiện tại cùng với type để có thể sử dụng.

Ví dụ:

use aggregator::{Summary, Tweet}; // <-- same scope

fn main() {

let tweet = Tweet {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from("of course, as you probably already know, people"),

reply: false,

retweet: false,

};

println!("1 new tweet: {}", tweet.summarize());

// 1 new tweet: horse_ebooks: of course, as you probably already know, people

}Rust Playground: https://play.rust-lang.org/?version=stable&mode=debug&edition=2021&gist=dc563051aecebae4344776c06fb1b49d

Chúng ta có thể implement trait cho mọi type khác bất kỳ, ví dụ implement Summary cho Vec<T> trong scope của crate hiện tại.

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize(&self) -> String;

}

impl<T> Summary for Vec<T> { // <-- local scope

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("There are {} items in vec", self.len())

}

}

fn main() {

let vec = vec![1i32, 2i32];

println!("{}", vec.summarize());

// There are 2 items in vec

}Rust Playground: https://play.rust-lang.org/?version=stable&mode=debug&edition=2021&gist=dcaa812fab222ec0c713a38b066bda20

Bạn sẽ không thể implement external traits trên external types.

Ví dụ ta không thể implement Display cho Vec<T> bởi vì

Display và Vec<T> được định nghĩa trong standard library,

trong trong crate hiện tại. Rule này giúp tránh chống chéo và chắc chắn

rằng không ai có thể break code của người khác và ngược lại.

Default Implementations

Đôi khi bạn cần có default behavior mà không cần phải implement content cho từng type mỗi khi cần sử dụng:

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

String::from("(Read more...)")

}

}

pub struct NewsArticle {

pub headline: String,

pub location: String,

pub author: String,

pub content: String,

}

impl Summary for NewsArticle {}; // <-- sử dụng {}

fn main() {

let article = NewsArticle { ... };

println!("New article: {}", article.summarize());

// New article: (Read more...)

}Traits as Parameters

Trở lại ví dụ Typescript ở đầu tiên, với Trait bạn đã có thể define một function chấp nhận tham số là nhiều kiểu dữ liệu khác nhau. Nói theo một cách khác, bạn không cần biết kiểu dữ liệu, bạn cần biết kiểu dữ liệu đó mang các behavior nào thì đúng hơn.

fn notify(data: &impl Summary) {

println!("News: {}", data.summarize());

}

fn main() {

let news = NewsArticle {};

notify(news);

}Ở đây, thay vì cần biết data là type nào (NewsArticle hay Tweet?),

ta chỉ cần cho Rust compiler biết là notify sẽ chấp nhận mọi

type có implement trait Summary, mà trait Summary có behavior .summarize(),

do đó ta có thể sử dụng method .summary() bên trong function.

Trait Bound

Một syntax sugar khác mà ta có thể sử dụng thay cho &impl Summary ở trên,

gọi là trait bound, bạn sẽ bắt gặp nhiều trong Rust document:

pub fn notify<T: Summary>(item: &T) {

println!("News: {}", item.summarize());

}Đầu tiên chúng ta định nghĩa trait bound bằng cách định nghĩa

một generic type parameter trước, sau đó là : trong ngoặc < và >.

Ta có thể đọc là: item có kiểu generic là T và T phải được impl Summary.

notify<T>(khai báo generic typeTnotify<T: Summary>(generic type được implementtrait Summary

Cú pháp này có thể dài hơn và không dễ đọc như &impl Summary, nhưng hãy xem ví dụ dưới đây:

pub fn notify(item1: &impl Summary, item2: &impl Summary) {} // (1)

pub fn notify<T: Summary>(item1: &T, item2: &T) {} // (2)Dùng trait bound giúp ta tái sử dụng lại T,

mà còn giúp force item1 và item2 có cùng kiểu dữ liệu,

đây là cách duy nhất (cả 2 đều là NewsArticle hoặc cả 2 đều là Tweet) mà (1) không thể.

Specifying Multiple Trait Bounds with the + Syntax

Ta có cú pháp + nếu muốn generic T có được impl nhiều trait khác nhau.

Ví dụ ta muốn item phải có cả Summary lẫn Display

pub fn notify(item: &(impl Summary + Display)) {}

pub fn notify<T: Summary + Display>(item: &T) {}where Clauses

Đôi khi bạn sẽ có nhiều genenic type, mỗi generic type lại có nhiều trait bound,

khiến code khó đọc. Rust có một cú pháp where cho phép định nghĩa trait bound

phía sau function signature. Ví dụ:

fn some_function<T: Display + Clone, U: Clone + Debug>(t: &T, u: &U) -> i32 {Với where clause:

fn some_function<T, U>(t: &T, u: &U) -> i32

where T: Display + Clone,

U: Clone + Debug,

{Returning Types that Implement Traits

Chúng ta cũng có thể sử dụng impl Trait cho giá trị được trả về của function.

fn returns_summarizable() -> impl Summary {

Tweet {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from("ahihi"),

reply: false,

retweet: false,

}

}Được đọc là: function returns_summarizable() trả về bất kỳ kiểu dữ liệu nào có impl Summary.

Tuy nhiên bạn chỉ có thể return về hoặc Tweet

hoặc NewsArticle do cách implement của compiler. Code sau sẽ có lỗi:

fn returns_summarizable(switch: bool) -> impl Summary {

if switch { NewsArticle {} }

else { Tweet {} }

}Rust Book có một chương riêng để xử lý vấn đề này: Chapter 17: Using Trait Objects That Allow for Values of Different Types

Using Trait Bounds to Conditionally Implement Methods

Ta có thể implement 1 method có điều kiện cho bất kỳ type nào có implement một trait khác cụ thể. Ví dụ để dễ hiểu hơn dưới đây:

use std::fmt::Display;

struct Pair<T> {

x: T,

y: T,

}

impl<T> Pair<T> {

fn new(x: T, y: T) -> Self {

Self { x, y }

}

}

impl<T: Display + PartialOrd> Pair<T> {

fn cmp_display(&self) {

if self.x >= self.y {

println!("The largest member is x = {}", self.x);

} else {

println!("The largest member is y = {}", self.y);

}

}

}impl<T> Pair<T> implement function new trả về kiểu dữ liệu Pair<T> với T là generic (bất kỳ kiểu dữ liệu nào.

impl<T: Display + PartialOrd> Pair<T> implement function cmp_display

cho mọi generic T với T đã được implement Display + PartialOrd

trước đó rồi (do đó mới có thể sử dụng các behavior của

Display (println!("{}")) và PartialOrd (>, <, …) được.

Blanket implementations

Ta cũng có thể implement 1 trait có điều kiện cho bất kỳ kiểu dữ liệu nào có implement một trait khác rồi. Implementation của một trait cho 1 kiểu dữ liệu khác thỏa mãn trait bound được gọi là blanket implementations và được sử dụng rộng rãi trong Rust standard library. Hơi xoắn não nhưng hãy xem ví dụ dưới đây.

Ví dụ: ToString trait trong

Rust standard library,

nó được implement cho mọi kiểu dữ liệu nào có được implement Display trait.

impl<T: Display> ToString for T {

// --snip--

}Có nghĩa là, với mọi type có impl Display, ta có hiển nhiên thể sử dụng được các thuộc tính của trait ToString.

let s = 3.to_string(); // do 3 thoaỏa manãn DisplayDo 3 thỏa mãn điều kiện là đã được impl Display for i32.

(https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/fmt/trait.Display.html#impl-Display-11)

Trait Inheritance

pub trait B: A {}Cái này không hẳn gọi là Trait Inheritance, cái này đúng hơn gọi là “cái nào implement cái B thì cũng nên implement cái A”. A và B vẫn là 2 trait độc lập nên vẫn phải implemenet cả 2.

impl B for Z {}

impl A for Z {}Inheritance thì không được khuyến khích sử dụng.

Supertraits

Rust không có khái niệm “kế thừa” như trong OOP. Nhưng bạn có thể định nghĩa một trait là một tập hợp của các trait khác.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

trait Person {

fn name(&self) -> String;

}

// Person là một supertrait của Student.

// Implement Student yêu cầu bạn phải cũng phải impl Person.

trait Student: Person {

fn university(&self) -> String;

}

trait Programmer {

fn fav_language(&self) -> String;

}

// CompSciStudent (computer science student) là một subtrait

// của cả Programmer và Student.

//

// Implement CompSciStudent yêu cầu bạn phải impl tất cả supertraits.

trait CompSciStudent: Programmer + Student {

fn git_username(&self) -> String;

}

fn comp_sci_student_greeting(student: &dyn CompSciStudent) -> String {

format!(

"My name is {} and I attend {}. My favorite language is {}. My Git username is {}",

student.name(),

student.university(),

student.fav_language(),

student.git_username()

)

}

}Auto Traits

Auto traits là các trait đánh dấu (marker trait) được tự động triển khai cho mọi kiểu dữ liệu,

trừ khi kiểu dữ liệu hoặc một kiểu dữ liệu mà nó chứa được khai báo tường minh là không impl bằng cách sử dụng negative_impls.

Ta cần bật feature auto_traits để khai báo auto trait.

#![allow(unused)]

#![feature(auto_traits)]

fn main() {

auto trait Valid {}

}Sau đó, ta có thể triển khai trait Valid cho các kiểu dữ liệu khác nhau:

#![feature(auto_traits)]

#![feature(negative_impls)]

auto trait Valid {}

struct True;

struct False;

// Negative impl

// Có nghĩa là Valid không được auto impl cho struct False

impl !Valid for False {}

// Nếu T được impl trait Valid, thì MaybeValid<T> cũng được impl trait Valid

struct MaybeValid<T>(T);

fn must_be_valid<T: Valid>(_t: T) { }

fn main() {

// Hoạt động

must_be_valid(MaybeValid(True));

// Báo lỗi - do `False` không được impl trait Valid

// must_be_valid(MaybeValid(False));

}Auto trait Valid, sẽ tự động impl cho mọi struct, enum, …

References

- https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/unstable-book/language-features/auto-traits.html

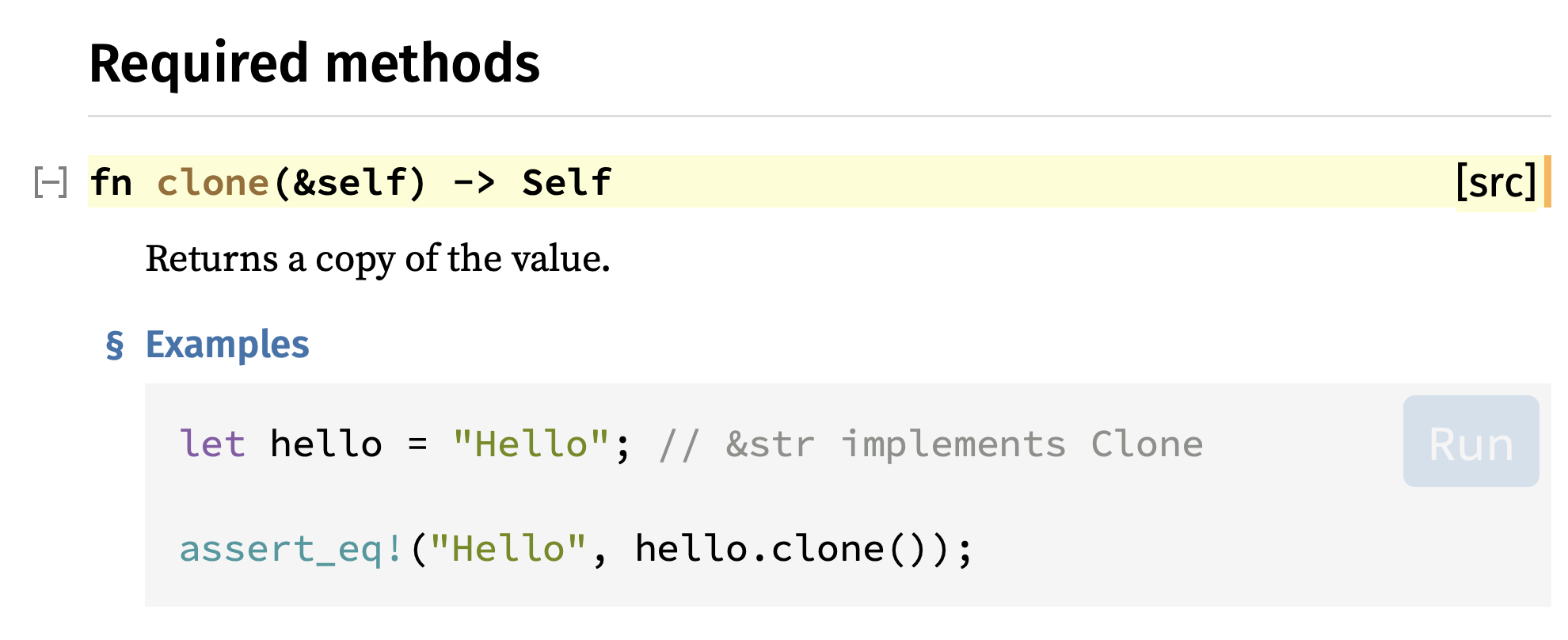

Copy, Clone

Có một số kiểu dữ liệu trong Rust rất đơn giản (simple types),

bao gồm integers, floats, booleans (true và false), và char.

Các simple types này nằm trên stack bởi vì complier biết chính xác size của nó.

Chúng được gọi là copy types. Bởi vì nó simple và nhỏ gọn nên dễ dàng để copy,

do đó compiler luôn copy nếu bạn bỏ nó vào function.

Làm sao để biết đọc một kiểu dữ liệu có được implement Copy hay không.

Bạn có thể xem trong Rust document. Ví dụ char:

https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/primitive.char.html

Nếu bạn thấy:

- Copy: có thể được copy nếu bạn bỏ nó vào function.

- Display: bạn có thể sử dụng

{}để print. - Debug: bạn có thể sử dụng

{:?}để print.

fn prints_number(number: i32) {

println!("{}", number);

}

fn main() {

let my_number = 8;

prints_number(my_number); // Prints 8. prints_number gets a copy of my_number

prints_number(my_number); // Prints 8 again.

// No problem, because my_number is copy type!

}Do i32 được Copy nên chúng ta có thể sử dụng my_number nhiều lần mà không cần borrow & như struct.

Clone trait

Nếu bạn đọc document của String: https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/string/struct.String.html

String không được implement Copy, thay vào đó là Clone. Clone cũng giúp copy giá trị nhưng sẽ cần rất nhiều memory, và ta phải tự gọi method .clone() chứ Rust sẽ không tự Clone.

fn prints_country(country_name: String) {

println!("{}", country_name);

}

fn main() {

let country = String::from("Duyet");

prints_country(country);

prints_country(country); // ⚠️

}Sẽ báo lỗi, theo như compiler giải thích rằng country là String và không được implement Copy nên country bị move vào trong function. Do đó ta không thể sử dụng country được nữa.

error[E0382]: use of moved value: `country`

--> src/main.rs:8:20

|

6 | let country = String::from("Duyet");

| ------- move occurs because `country` has type `String`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

7 | prints_country(country);

| ------- value moved here

8 | prints_country(country); // ⚠️

| ^^^^^^^ value used here after move

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0382`.Có hai cách:

(1) Sử dụng .clone()

fn prints_country(country_name: String) {

println!("{}", country_name);

}

fn main() {

let country = String::from("Duyet");

prints_country(country.clone()); // <-- clone

prints_country(country);

}String rất lớn, do đó .copy() sẽ tốn rất nhiều bộ nhớ. Sử dụng & để reference sẽ nhanh hơn, nếu có thể.

(2) Sử dụng & reference

fn prints_country(country_name: &String) {

println!("{}", country_name);

}

fn main() {

let country = String::from("Duyet");

prints_country(&country);

prints_country(&country);

}Bonus: String và &str

Nếu bạn có một String và & reference, Rust sẽ convert nó thành &str khi bạn cần.

fn prints_country(country_name: &str) {

println!("{}", country_name);

}

fn main() {

let country = String::from("Duyet");

prints_country(&country);

prints_country(&country);

}&str là một kiểu hơi phức tạp.

- Nó có thể vừa là String literals

let s = "I am &str";. Trường hợp nàyscó kiểu&'staticbởi vì nó được ghi trực tiếp vào binary. &strcũng có thể là borrowed củastrhoặcString.

Bonus: String và &str

Nếu bạn có một String và & reference, Rust sẽ convert nó thành &str khi bạn cần.

fn prints_country(country_name: &str) {

println!("{}", country_name);

}

fn main() {

let country = String::from("Duyet");

prints_country(&country);

prints_country(&country);

}&str là một kiểu hơi phức tạp.

- Nó có thể vừa là String literals

let s = "I am &str";. Trường hợp nàyscó kiểu&'staticbởi vì nó được ghi trực tiếp vào binary. &strcũng có thể là borrowed củastrhoặcString.

FromStr

FromStr là một trait để khởi tạo instance từ string trong Rust, nó tương đương abstract class nếu bạn có background OOP.

pub trait FromStr {

type Err;

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err>;

}Thường phương thức from_str của FromStr thường được ngầm định

sử dụng thông qua phương thức

parse

của str. Ví dụ:

// Thay vì

let one = u32::from_str("1");

// thì sử dụng phương thức parse

let one: u32 = "1".parse().unwrap();

assert_eq!(1, one);

// parse() sử dụng turbofish ::<>

let two = "2".parse::<u32>();

assert_eq!(Ok(2), two);

let nope = "j".parse::<u32>();

assert!(nope.is_err());parse là một phương thức general nên thường được sử dụng với kiểu dữ liệu

như trên hoặc sử dụng turbofish ::<> để thuật toán inference

có thể hiểu để parse thành đúng kiểu bạn cần.

Parse str to Struct

Bạn có 1 struct và muốn parse 1 str thành struct đó, bạn sẽ cần impl trait FromStr

use std::str::FromStr;

use std::num::ParseIntError;

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq)]

struct Point {

x: i32,

y: i32

}

impl FromStr for Point {

type Err = ParseIntError;

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

let coords: Vec<&str> = s.trim_matches(|p| p == '(' || p == ')' )

.split(',')

.collect();

let x_fromstr = coords[0].parse::<i32>()?;

let y_fromstr = coords[1].parse::<i32>()?;

Ok(Point { x: x_fromstr, y: y_fromstr })

}

}

// Có nhiều cách

let p: Point = "(1,2)".parse();

let p = "(1,2)".parse::<Point>();

let p = Point::from_str("(1,2)");

assert_eq!(p.unwrap(), Point{ x: 1, y: 2} )Parse str to Enum

Một điều mình nhận thấy để code dễ đọc, dễ maintain hơn là ta nên sử dụng Enum thay cho string để so sánh giá trị. Ví dụ:

fn print(color: &str, text: &str) { ... }

print("Foobar", "blue");Thay vì đó mà hãy sử dụng enum:

enum Color { Red, Green, CornflowerBlue }

fn print(color: Color, text: &str) { ... }

print(Green, "duyet");Cũng nên hạn chế sử dụng quá nhiều Boolean, thực tế Boolean cũng chỉ là 1 enum

enum bool { true, false }Thay vào đó hãy tự định nghĩa enum cho các ngữ cảnh khác nhau để code dễ đọc hơn:

enum EnvVars { Clear, Inherit }

enum DisplayStyle { Color, Monochrome }Chúng ta implement std::str::FromStr trait như sau:

use std::str::FromStr;

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq)]

enum Color {

Red,

Green,

Blue

}

impl FromStr for Color {

type Err = ();

fn from_str(input: &str) -> Result<Color, Self::Err> {

match input {

"red" => Ok(Color::Red),

"green" => Ok(Color::Green),

"blue" => Ok(Color::Blue),

_ => Err(()),

}

}

}

let c: Color = "red".parse().unwrap();

assert_eq!(c, Color::Red);References

- Trait

- https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/std/primitive.str.html#method.parse

- https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/std/str/trait.FromStr.html

Display

Trait Display cho phép bạn định nghĩa cách một type được hiển thị khi sử dụng format string {}. Đây là trait quan trọng để tạo ra output thân thiện với người dùng.

Display vs Debug

Rust có hai trait chính cho việc formatting:

| Trait | Format Specifier | Mục đích |

|---|---|---|

Debug | {:?} hoặc {:#?} | Development, debugging (technical output) |

Display | {} | User-facing output (human-readable) |

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

fn main() {

let p = Point { x: 3, y: 4 };

// Debug - technical output

println!("{:?}", p); // Point { x: 3, y: 4 }

// Display - compile error! Display không được derive tự động

// println!("{}", p); // ❌ Error: `Point` doesn't implement `Display`

}Implement Display

Để implement Display, bạn cần định nghĩa method fmt:

use std::fmt;

struct Point {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

impl fmt::Display for Point {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

write!(f, "({}, {})", self.x, self.y)

}

}

fn main() {

let p = Point { x: 3, y: 4 };

println!("{}", p); // In ra: (3, 4)

}Ví dụ với Enum

use std::fmt;

enum Status {

Active,

Inactive,

Pending,

}

impl fmt::Display for Status {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

match self {

Status::Active => write!(f, "Đang hoạt động"),

Status::Inactive => write!(f, "Không hoạt động"),

Status::Pending => write!(f, "Đang chờ xử lý"),

}

}

}

fn main() {

let status = Status::Active;

println!("Trạng thái: {}", status); // In ra: Trạng thái: Đang hoạt động

}Ví dụ với Struct phức tạp

use std::fmt;

struct Person {

name: String,

age: u32,

email: String,

}

impl fmt::Display for Person {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

write!(

f,

"{} (tuổi {}) - Email: {}",

self.name, self.age, self.email

)

}

}

fn main() {

let person = Person {

name: String::from("Nguyễn Văn A"),

age: 25,

email: String::from("nguyenvana@example.com"),

};

println!("{}", person);

// In ra: Nguyễn Văn A (tuổi 25) - Email: nguyenvana@example.com

}Display với nhiều format options

Bạn có thể sử dụng các format options từ Formatter:

use std::fmt;

struct Currency {

amount: f64,

symbol: &'static str,

}

impl fmt::Display for Currency {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

// Sử dụng precision từ format string

if let Some(precision) = f.precision() {

write!(f, "{}{:.precision$}", self.symbol, self.amount, precision = precision)

} else {

write!(f, "{}{:.2}", self.symbol, self.amount)

}

}

}

fn main() {

let price = Currency { amount: 1234.5678, symbol: "$" };

println!("{}", price); // $1234.57 (mặc định 2 chữ số)

println!("{:.0}", price); // $1235 (không có phần thập phân)

println!("{:.4}", price); // $1234.5678 (4 chữ số thập phân)

}Display với Vec và collection

use std::fmt;

struct NumberList {

numbers: Vec<i32>,

}

impl fmt::Display for NumberList {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

let numbers_str: Vec<String> = self.numbers

.iter()

.map(|n| n.to_string())

.collect();

write!(f, "[{}]", numbers_str.join(", "))

}

}

fn main() {

let list = NumberList {

numbers: vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

};

println!("{}", list); // In ra: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

}Kết hợp Debug và Display

Thường thì bạn implement cả hai:

use std::fmt;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct User {

id: u32,

username: String,

is_active: bool,

}

impl fmt::Display for User {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

write!(f, "@{}", self.username)

}

}

fn main() {

let user = User {

id: 1,

username: String::from("duyet"),

is_active: true,

};

// Display - user-facing

println!("User: {}", user);

// In ra: User: @duyet

// Debug - developer-facing

println!("Debug: {:?}", user);

// In ra: Debug: User { id: 1, username: "duyet", is_active: true }

}Error handling với Display

Display thường được sử dụng khi implement custom error types:

use std::fmt;

use std::error::Error;

#[derive(Debug)]

enum MyError {

NotFound(String),

InvalidInput(String),

NetworkError,

}

impl fmt::Display for MyError {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

match self {

MyError::NotFound(item) => write!(f, "Không tìm thấy: {}", item),

MyError::InvalidInput(msg) => write!(f, "Dữ liệu không hợp lệ: {}", msg),

MyError::NetworkError => write!(f, "Lỗi kết nối mạng"),

}

}

}

impl Error for MyError {}

fn main() {

let error = MyError::NotFound(String::from("user.txt"));

println!("Lỗi: {}", error);

// In ra: Lỗi: Không tìm thấy: user.txt

}Display với nested types

use std::fmt;

struct Address {

street: String,

city: String,

}

impl fmt::Display for Address {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

write!(f, "{}, {}", self.street, self.city)

}

}

struct Company {

name: String,

address: Address,

}

impl fmt::Display for Company {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

write!(f, "{} tại {}", self.name, self.address)

}

}

fn main() {

let company = Company {

name: String::from("Rust Corp"),

address: Address {

street: String::from("123 Nguyễn Huệ"),

city: String::from("TP.HCM"),

},

};

println!("{}", company);

// In ra: Rust Corp tại 123 Nguyễn Huệ, TP.HCM

}So sánh với các ngôn ngữ khác

Python

class Point:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def __str__(self): # Tương đương Display

return f"({self.x}, {self.y})"

def __repr__(self): # Tương đương Debug

return f"Point(x={self.x}, y={self.y})"

p = Point(3, 4)

print(p) # Gọi __str__

print(repr(p)) # Gọi __repr__

Java

class Point {

private int x, y;

public Point(int x, int y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

@Override

public String toString() { // Tương đương Display

return String.format("(%d, %d)", x, y);

}

}

Point p = new Point(3, 4);

System.out.println(p); // Gọi toString()

Rust - Type Safe

Ưu điểm của Rust:

- Compiler bắt buộc phải implement Display nếu muốn dùng

{} - Không thể vô tình in ra kiểu dữ liệu chưa implement Display

- Phân biệt rõ ràng giữa Debug (technical) và Display (user-facing)

Best Practices

1. Display cho user, Debug cho developer

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// ✅ Tốt

impl fmt::Display for User {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

write!(f, "{}", self.username) // Simple, user-friendly

}

}

// ❌ Tránh

impl fmt::Display for User {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

write!(f, "User {{ id: {}, username: {} }}", self.id, self.username)

// Quá technical, nên dùng Debug

}

}

}2. Concise và meaningful

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// ✅ Tốt

write!(f, "Error: File not found")

// ❌ Tránh - quá dài dòng

write!(f, "An error has occurred during the file reading operation: The specified file could not be found in the filesystem")

}3. Consistent formatting

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// ✅ Tốt - consistent format cho cùng type

impl fmt::Display for Date {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

write!(f, "{:04}-{:02}-{:02}", self.year, self.month, self.day)

}

}

}Tổng kết

Display trait là công cụ mạnh mẽ để:

- Tạo output thân thiện với người dùng

- Implement custom formatting cho types

- Tích hợp với error handling

- Cung cấp API nhất quán cho printing

Khi implement Display:

- Giữ output đơn giản, dễ đọc

- Dùng cho user-facing messages

- Kết hợp với Debug cho developer output

- Follow consistent formatting conventions

References

Enum

Giống như các ngôn ngữ khác, Enum là một kiểu giá trị đơn, chứa các biến thể (variants).

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

enum Day {

Sunday,

Monday,

Tuesday,

Wednesday,

Thursday,

Friday,

Saturday

}

let today = Day::Sunday;

}Enum variant có thể là

- unit variant

- tuple variant

- struct variant

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

enum FlashMessage {

Success, // unit variant

Error(String), // tuple variant

Warning { category: i32, message: String }, // struct variant

}

}match Enum

match cực kỳ mạnh và được dùng trong Rust phổ biến.

Ví dụ sau là cách để kiểm tra một giá trị enum là variant nào.

enum Coin {

Penny,

Nickel,

Dime,

Quarter,

}

fn value_in_cents(coin: Coin) -> u8 {

match coin {

Coin::Penny => 1,

Coin::Nickel => 5,

Coin::Dime => 10,

Coin::Quarter => 25,

}

}

fn main() {}match còn có thể trích xuất các giá trị từ tuple variant hoặc struct variant.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

enum FlashMessage {

Success, // unit variant

Error(String), // tuple variant

Warning { category: i32, message: String }, // struct variant

}

fn format_message(message: FlashMessage) -> String {

match message {

FlashMessage::Success => "success".to_string(),

FlashMessage::Error(err) => format!("My error: {}", err),

FlashMessage::Warning{ category, message } => format!("Warn: {} (category: {})", message, category),

}

}

let m = format_message(FlashMessage::Error("something went wrong".to_string()));

println!("{m}");

}References

- https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch06-02-match.html

- https://blog.logrocket.com/rust-enums-and-pattern-matching/

use Enum::

Ta có thể mang variants ra ngoài scope của enum bằng use.

enum Coin {

Penny,

Nickel,

Dime,

Quarter,

}

// hoặc

// use self::Coin::{Penny, Nickel, Dime, Quarter};

use Coin::*;

fn value_in_cents(coin: Coin) -> u8 {

match coin {

Penny => 1,

Nickel => 5,

Dime => 10,

Quarter => 25,

}

}

fn main() {

assert_eq!(value_in_cents(Penny), 1);

assert_eq!(value_in_cents(Coin::Penny), 1);

}impl Enum

Ta cũng có thể impl cho enum giống như struct.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

enum Day {

Sunday,

Monday,

Tuesday,

Wednesday,

Thursday,

Friday,

Saturday

}

// impl enum

impl Day {

fn today(self) -> Self {

self

}

}

// Trait

trait DayOff {

fn day_off(self);

}

// impl trait for enum

impl DayOff for Day {

fn day_off(self) {

match self.today() {

Self::Sunday | Self::Saturday => println!("day off"),

_ => println!("noooo"),

}

}

}

let today = Day::Sunday;

today.day_off();

}match Enum

match cực kỳ mạnh và được dùng trong Rust phổ biến.

Ví dụ sau là cách để kiểm tra một giá trị enum là variant nào.

enum Coin {

Penny,

Nickel,

Dime,

Quarter,

}

fn value_in_cents(coin: Coin) -> u8 {

match coin {

Coin::Penny => 1,

Coin::Nickel => 5,

Coin::Dime => 10,

Coin::Quarter => 25,

}

}

fn main() {}match còn có thể trích xuất các giá trị từ tuple variant hoặc struct variant.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

enum FlashMessage {

Success, // unit variant

Error(String), // tuple variant

Warning { category: i32, message: String }, // struct variant

}

fn format_message(message: FlashMessage) -> String {

match message {

FlashMessage::Success => "success".to_string(),

FlashMessage::Error(err) => format!("My error: {}", err),

FlashMessage::Warning{ category, message } => format!("Warn: {} (category: {})", message, category),

}

}

let m = format_message(FlashMessage::Error("something went wrong".to_string()));

println!("{m}");

}References

- https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch06-02-match.html

- https://blog.logrocket.com/rust-enums-and-pattern-matching/

use Enum::

Ta có thể mang variants ra ngoài scope của enum bằng use.

enum Coin {

Penny,

Nickel,

Dime,

Quarter,

}

// hoặc

// use self::Coin::{Penny, Nickel, Dime, Quarter};

use Coin::*;

fn value_in_cents(coin: Coin) -> u8 {

match coin {

Penny => 1,

Nickel => 5,

Dime => 10,

Quarter => 25,

}

}

fn main() {

assert_eq!(value_in_cents(Penny), 1);

assert_eq!(value_in_cents(Coin::Penny), 1);

}impl Enum

Ta cũng có thể impl cho enum giống như struct.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

enum Day {

Sunday,

Monday,

Tuesday,

Wednesday,

Thursday,

Friday,

Saturday

}

// impl enum

impl Day {

fn today(self) -> Self {

self

}

}

// Trait

trait DayOff {

fn day_off(self);

}

// impl trait for enum

impl DayOff for Day {

fn day_off(self) {

match self.today() {

Self::Sunday | Self::Saturday => println!("day off"),

_ => println!("noooo"),

}

}

}

let today = Day::Sunday;

today.day_off();

}Option

Nhiều ngôn ngữ sử dụng kiểu dữ liệu null hoặc nil hoặc undefined

để đại diện cho các giá trị rỗng hoặc không tồn tại, và sử dụng Exception

để xử lý lỗi. Rust bỏ qua hai khái niệm này, để tránh gặp phải các lỗi phổ biến

như null pointer exceptions, hay lộ thông tin nhạy cảm thông qua exceptions, …

Thay vào đó, Rust giới thiệu hai generic enums Option

và Result để giải quyết các vấn đề trên.

Trong hầu hết các ngôn ngữ họ C (C, C#, Java, …), để xác định một cái gì đó failed

hay không tìm được giá trị thỏa mãn, chúng ta thường trả về một giá trị “đặc biệt” nào đó.

Ví dụ indexOf() của Javascript scan một phần tử trong mảng,

trả về vị trí của phần tử đó trong mảng. Và trả về -1 nếu không tìm thấy.

Dẫn đến, ta sẽ thường thấy một số đoạn code như sau đây:

// Typescript

let sentence = "The fox jumps over the dog";

let index = sentence.indexOf("fox");

if (index > -1) {

let result = sentence.substr(index);

console.log(result);

}

Như bạn thấy -1 là một trường hợp đặc biệt cần xử lý.

Có khi nào bạn đã từng mắc lỗi ngớ ngẫn vì tưởng giá trị đặc biệt đó là 0 chưa?

// Typescript

if (index > 0) {

// 3000 days of debugging

}

"" hay null hay None cũng là một trong những trường hợp đặc biệt đó.

Bạn đã từng nghe đến Null References: The Billion Dollar Mistake?

Lý do cơ bản là không có gì chắc chắn và có thể ngăn bạn lại việc … quên xử lý mọi trường hợp giá trị đặc biệt, hoặc do chương trình trả về các giá trị đặc biệt không như mong đợi. Có nghĩa là ta có thể vô tình làm crash chương trình với một lỗi nhỏ ở bất kỳ đâu, ở bất kỳ thời điểm nào.

Rust làm điều này tốt hơn, chỉ với Option.

Một giá trị optional có thể mang một giá trị nào đó Some(something) hoặc không mang giá trị nào cả (None).

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// An output can have either Some value or no value/ None.

enum Option<T> { // T is a generic and it can contain any type of value.

Some(T),

None,

}

}Theo thiết kế, mặc định bạn sẽ không bao giờ lấy được giá trị bạn cần nếu không xử lý

các trường hợp có thể xảy ra với Option, là None chẳng hạn.

Điều này được bắt buộc bởi compiler lúc compile code,

có nghĩa là nếu bạn quên check, code sẽ không bao giờ được compile.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let sentence = "The fox jumps over the dog";

let index = sentence.find("fox");

if let Some(fox) = index {

let words_after_fox = &sentence[fox..];

println!("{}", words_after_fox);

}

}Cách sử dụng Option

Option là standard library, do đã được

preludes

nên chúng ta không cần khai báo trước khi sử dụng. Ngoài enum

Option thì các variant của nó cũng đã được preludes

sẵn như Some

và None.

Ví dụ, ta có một function tính giá trị chia hai số, đôi khi sẽ không tìm ra được kết quả, ta sử dụng Some như sau:

fn get_id_from_name(name: &str) -> Option<i32> {

if !name.starts_with('d') {

return None;

}

Some(123)

}

fn main() {

let name = "duyet";

match get_id_from_name(name) {

Some(id) => println!("User = {}", id),

_ => println!("Not found"),

}

}Ta thường sử dụng match để bắt giá trị trả về (Some hoặc None).

Bạn sẽ bắt gặp rất nhiều method khác nhau để xử lý giá trị của Option

Option method overview: https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/option/#method-overview

.unwrap()

Trả về giá trị nằm trong Some(T). Nếu giá trị là None thì panic chương trình.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let x = Some("air");

assert_eq!(x.unwrap(), "air");

let x: Option<&str> = None;

assert_eq!(x.unwrap(), "air"); // panic!

}.expect()

Giống .unwrap(), nhưng khi panic thì Rust sẽ kèm theo message

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let x: Option<&str> = None;

x.expect("fruits are healthy"); // panics: `fruits are healthy`

}.unwrap_or()

Trả về giá trị nằm trong Some, nếu không trả về giá trị nằm trong or

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

assert_eq!(Some("car").unwrap_or("bike"), "car");

}.unwrap_or_default()

Trả về giá trị nằm trong Some, nếu không trả về giá default.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let good_year_from_input = "1909";

let bad_year_from_input = "190blarg";

let good_year = good_year_from_input.parse().ok().unwrap_or_default();

let bad_year = bad_year_from_input.parse().ok().unwrap_or_default();

assert_eq!(1909, good_year);

assert_eq!(0, bad_year);

}.ok_or()

Convert Option<T> sang Result<T, E>,

mapping Some(v)

thành Ok(v)

và None

sang Err(err).

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let x = Some("foo");

assert_eq!(x.ok_or(0), Ok("foo"));

}match

Chúng ta có thể sử dụng pattern matching để code dễ đọc hơn

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn get_name(who: Option<String>) -> String {

match who {

Some(name) => format!("Hello {}", name),

None => "Who are you?".to_string(),

}

}

get_name(Some("duyet"));

}if let Some(x) = x

Có thể bạn sẽ gặp pattern này nhiều khi đọc code Rust.

Nếu giá trị của x là Some thì sẽ destruct

giá trị đó bỏ vào biến x nằm trong scope của if.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn get_data() -> Option<String> {

Some("ok".to_string())

}

if let Some(data) = get_data() {

println!("data = {}", data);

} else {

println!("no data");

}

}unwrap()

.unwrap()

Trả về giá trị nằm trong Some(T). Nếu giá trị là None thì panic chương trình.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let x = Some("air");

assert_eq!(x.unwrap(), "air");

let x: Option<&str> = None;

assert_eq!(x.unwrap(), "air"); // panic!

}expect()

.expect()

Giống .unwrap(), nhưng khi panic thì Rust sẽ kèm theo message

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let x: Option<&str> = None;

x.expect("fruits are healthy"); // panics: `fruits are healthy`

}unwrap_or_default()

.unwrap_or_default()

Trả về giá trị nằm trong Some, nếu không trả về giá default.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let good_year_from_input = "1909";

let bad_year_from_input = "190blarg";

let good_year = good_year_from_input.parse().ok().unwrap_or_default();

let bad_year = bad_year_from_input.parse().ok().unwrap_or_default();

assert_eq!(1909, good_year);

assert_eq!(0, bad_year);

}if let Some(x) = x

if let Some(x) = x

Có thể bạn sẽ gặp pattern này nhiều khi đọc code Rust.

Nếu giá trị của x là Some thì sẽ destruct

giá trị đó bỏ vào biến x nằm trong scope của if.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn get_data() -> Option<String> {

Some("ok".to_string())

}

if let Some(data) = get_data() {

println!("data = {}", data);

} else {

println!("no data");

}

}Result

Tương tự như Option.

Một kết quả trả về (Result)

của một function thường sẽ có hai trường hợp:

Result là một phiên bản cao cấp hơn của Option.

Nó mô tả lỗi gì đang xảy ra thay vì khả năng tồn tại giá trị hay không.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

enum Result<T, E> {

Ok(T),

Err(E),

}

}Ví dụ

fn get_id_from_name(name: &str) -> Result<i32, &str> {

if !name.starts_with('d') {

return Err("not found");

}

Ok(123)

}

fn main() -> Result<(), &'static str> {

let name = "duyet";

match get_id_from_name(name) {

Ok(id) => println!("User = {}", id),

Err(e) => println!("Error: {}", e),

};

Ok(())

}Như bạn thấy thì main() cũng có thể return về Result<(), &'static str>

.unwrap()

Ví dụ trên nhưng sử dụng .unwrap() , chủ động panic (crash) dừng chương trình nếu gặp lỗi.

fn main() -> Result<(), &'static str> {

let who = "duyet";

let age = get_age(who).unwrap();

println!("{} is {}", who, age);

Ok(())

}.expect()

Giống như unwrap(): chủ động panic (crash) dừng chương trình nếu gặp lỗi và kèm theo message. Sẽ rất có ích, nhất là khi có quá nhiều unwrap, bạn sẽ không biết nó panic ở đâu.

fn main() -> Result<(), &'static str> {

let who = "ngan";

let age = get_age(who).expect("could not get age");

println!("{} is {}", who, age);

Ok(())

}Xem thêm mọi method khác của Result tại đây.

Convert Result -> Option

Đôi khi bạn sẽ cần convert từ:

Ok(v)–>Some(v)- hoặc ngược lại,

Err(e)–>Some(e)

.ok()

// .ok(v) = Some(v)

let x: Result<u32, &str> = Ok(2);

assert_eq!(x.ok(), Some(2));

let y: Result<u32, &str> = Err("Nothing here");

assert_eq!(y.ok(), None);.err()

// .err()

let x: Result<u32, &str> = Ok(2);

assert_eq!(x.err(), None);

let x: Result<u32, &str> = Err("Nothing here");

assert_eq!(x.err(), Some("Nothing here"));Toán tử ?

Khi viết code mà có quá nhiều functions trả về Result, việc handle Err sẽ khá nhàm chán.

Toán tử chấm hỏi ? cho phép dừng function tại vị trí đó và return cho function cha nếu Result ở vị trí đó là Err.

Nó sẽ thay thế đoạn code sau:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::prelude::*;

use std::io;

struct Info {

name: String,

age: i32,

rating: i32,

}

fn write_info(info: &Info) -> io::Result<()> {

// Early return on error

let mut file = match File::create("my_best_friends.txt") {

Err(e) => return Err(e),

Ok(f) => f,

};

if let Err(e) = file.write_all(format!("name: {}\n", info.name).as_bytes()) {

return Err(e)

}

if let Err(e) = file.write_all(format!("age: {}\n", info.age).as_bytes()) {

return Err(e)

}

if let Err(e) = file.write_all(format!("rating: {}\n", info.rating).as_bytes()) {

return Err(e)

}

Ok(())

}

}thành

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::prelude::*;

use std::io;

struct Info {

name: String,

age: i32,

rating: i32,

}

fn write_info(info: &Info) -> io::Result<()> {

let mut file = File::create("my_best_friends.txt")?;

// Early return on error

file.write_all(format!("name: {}\n", info.name).as_bytes())?;

file.write_all(format!("age: {}\n", info.age).as_bytes())?;

file.write_all(format!("rating: {}\n", info.rating).as_bytes())?;

Ok(())

}

}Gọn đẹp hơn rất nhiều.

Toán tử ? sẽ unwrap giá trị Ok, hoặc return giá trị Err ở vị trí gần toán tử đó.

? chỉ có thể được dùng trong function có kiểu dữ liệu trả về là Result.

Convert Result -> Option

Đôi khi bạn sẽ cần convert từ:

Ok(v)–>Some(v)- hoặc ngược lại,

Err(e)–>Some(e)

.ok()

// .ok(v) = Some(v)

let x: Result<u32, &str> = Ok(2);

assert_eq!(x.ok(), Some(2));

let y: Result<u32, &str> = Err("Nothing here");

assert_eq!(y.ok(), None);.err()

// .err()

let x: Result<u32, &str> = Ok(2);

assert_eq!(x.err(), None);

let x: Result<u32, &str> = Err("Nothing here");

assert_eq!(x.err(), Some("Nothing here"));Toán tử ?

Khi viết code mà có quá nhiều functions trả về Result, việc handle Err sẽ khá nhàm chán.

Toán tử chấm hỏi ? cho phép dừng function tại vị trí đó và return cho function cha nếu Result ở vị trí đó là Err.

Nó sẽ thay thế đoạn code sau:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::prelude::*;

use std::io;

struct Info {

name: String,

age: i32,

rating: i32,

}

fn write_info(info: &Info) -> io::Result<()> {

// Early return on error

let mut file = match File::create("my_best_friends.txt") {

Err(e) => return Err(e),

Ok(f) => f,

};

if let Err(e) = file.write_all(format!("name: {}\n", info.name).as_bytes()) {

return Err(e)

}

if let Err(e) = file.write_all(format!("age: {}\n", info.age).as_bytes()) {

return Err(e)

}

if let Err(e) = file.write_all(format!("rating: {}\n", info.rating).as_bytes()) {

return Err(e)

}

Ok(())

}

}thành

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::prelude::*;

use std::io;

struct Info {

name: String,

age: i32,

rating: i32,

}

fn write_info(info: &Info) -> io::Result<()> {

let mut file = File::create("my_best_friends.txt")?;

// Early return on error

file.write_all(format!("name: {}\n", info.name).as_bytes())?;

file.write_all(format!("age: {}\n", info.age).as_bytes())?;

file.write_all(format!("rating: {}\n", info.rating).as_bytes())?;

Ok(())

}

}Gọn đẹp hơn rất nhiều.

Toán tử ? sẽ unwrap giá trị Ok, hoặc return giá trị Err ở vị trí gần toán tử đó.

? chỉ có thể được dùng trong function có kiểu dữ liệu trả về là Result.

Generics

Generics là một khái niệm để tổng quát hóa các kiểu dữ liệu hoặc tính năng cho các trường hợp rộng hơn. Tổng quát hóa cực kỳ hữu ích trong việc giảm số lượng code duplication. Một trong những ví dụ phổ biến nhất của tổng quát hóa là tổng quát một function có thể input nhiều loại kiểu dữ liệu khác nhau (type parameters).

Generic type parameters thường được biểu diễn dưới dạng <T>.

Ví dụ, định nghĩa một generic function foo nhận một tham số T của mọi kiểu dữ liệu.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn foo<T>(arg: T) { ... }

}Xem các trang sau để biết chi tiết về generic type được ứng dụng trong các trường hợp khác nhau như thế nào.

Generic Functions

Định nghĩa một generic function bằng cách khai báo generic type <T> sau tên của function.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn foo<T>(x: T) {} // x có kiểu T, T là generic type

fn bar<T>(x: T, y: T) {} // x và y đều có kiểu T

fn baz<T, U>(x: T, y: U) {} // sử dụng nhiều generic type

}Gọi một generic function đôi khi yêu cầu chỉ định kiểu dữ liệu tường minh cho tham số đó. Đôi khi là do function được gọi trả về kiểu dữ liệu là generic, hoặc compiler không có đủ thông tin. Thực thi một function và chỉ định kiểu dữ liệu tường minh có cú pháp như sau:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

function_name::<A, B>()

}Ví dụ:

fn print_me<T: ToString>(content: T) {

println!("{}", content.to_string());

}

fn main() {

print_me::<i32>(100);

print_me::<u64>(1_000_000);

}Cú pháp <T: ToString> có nghĩa là: function print_me chấp nhận mọi tham số có

kiểu T, miễn sau T được implement trait

ToString.

Một ví dụ khác phức tạp hơn từ Rust By Example

struct A; // Type tường minh `A`.

struct S(A); // Type tường minh `S`.

struct SGen<T>(T); // Type Generic `SGen`.

// Các function sau sẽ take ownership của variable

// sau đó thoát ra khỏi scope {}, sau đó giải phóng variable.

// Định nghĩa function `reg_fn` nhận tham số `_s` có kiểu `S`.

// Không có `<T>` vì vậy đây không phải là một generic function.

fn reg_fn(_s: S) {}

// Định nghĩa function `gen_spec_t` nhận tham số `_s` có kiểu `SGen<T>`.

// Ở đây tường minh kiểu `A` cho `S`, và bởi vì `A` không được khai báo

// như là một generic type parameter cho `gen_spec_t`,

// nên đây cũng không phải là một generic function.

fn gen_spec_t(_s: SGen<A>) {}

// Định nghĩa function `gen_spec_i32` nhận tham số `_s` có kiểu `SGen<i32>`.

// Giống như ở trên, ta khai báo tường minh `i32` cho `T`.

// Bởi vì `i32` không phải là một a generic type, nên function này cũng không